Each day pours into the next relentlessly, it’s as if there’s only so much that 24 hours can handle. I can safely say that 25th April 2015 was the longest day of my life.

21–22 April

The bus journey from Varanasi lasted an exhausting 17 hours on treacherous road. We passed through a huge archway which read a curt ‘Indian Border Ends’, and I was finally in Kathmandu.

Suddenly I was acutely aware of the fact that it was finally happening- the lone-traveller-traveling-without-a-plan thing. I was venturing into a foreign country for the first time, about 3000 km away from home.

Kathmandu was warmer than I had expected. The city was colourful with temples and prayer flags. The air was thick with dust. The river carried mostly sewage. But the people were friendly and helpful. They struck up conversations easily, even with me, a total stranger. I fell in love with the place, instantly.

I felt I could spend hours just looking around in the red brick and carved wood Durbar Squares, watching people — old men, college students, families — sitting and passing time.

I struggled to pick up the language, and used the basic phrases in Nepali that I had saved on my phone. When the people I met learned that I was Indian they switched to fluent Hindi; only to be confused to find me still faltering. Being Tamilian, I have only a basic hold on Hindi, and it is as foreign a language for me as any other.

I had planned the trip such that I was to come to Kathmandu back on the last day, to take the bus back to Varanasi. I promised myself that before I went back to India, I would climb the two hundred feet high Dharahara Tower to see the magnificent panorama, and also visit the pretty little temple which I had passed by so often during my walks in the city, the one which no one seemed to go into.

23–24 April

Bhaktapur, not far from the capital, is a UNESCO World Heritage Site with red brick pavements, narrow branching lanes, ancient temples and outbursts of flamboyant woodwork even on the most modest old houses.

The traditional Tibetan Buddhist art of painting called Thanka was being taught at many small schools around the square. One could, I thought, spend a lifetime trying to master these intricate art forms. The shop nearby selling these Thanka paintings had a massive yak skin canvas with concentric circles of Tibetan prayers neatly painted on it in gold.

I met Gyanu Maya, a 75 year old lady, who sold jewellery that she had made herself. While I bought something from her, she made small talk in Nepali, not noticing that I didn’t understand a word.

Each section of the town was meant for different purposes- whole neighbourhoods for people who made pottery, jewellery, carpets, paintings, etc.

I wondered how different life would be if I lived in this town, a cultural hub and an architectural marvel!

A bus ride took me to a village called Nagarkot, farther up in the hills. There were few tourists here.

My first glimpse of the distant snow on massive peaks was overwhelming. It was slightly worrying to acknowledge, as a student of Medicine, that just the sigh of these beautiful giants could be therapeutic.

Later I walked through the forest to Kattike, a small village that is accessible only by foot and maybe a courageous driver. I stopped at the first house to ask for water and directions. The father and son there were unwilling to talk. I tried my broken Nepali, and then there was no stopping them! I realised they were just uncomfortable with English, but were actually very friendly people. We spoke about Nepal, its economy, their food and habits. As we drew maps of our countries trying to show our hometowns, they served me their local drinks, chyang and raksi. Nyang Pasang Sherpa, the father, had climbed Mount Everest four times!

How long does it take for three people to become good friends? Three hours and some alcohol, I would say.

25 April 2015

Despite sore muscles, I made up my mind to trek to the foothills on the other side of the valley. I set out for Dhulikel, the next town, with my backpack. After three hours I realised I was lost. A helpful young man pulled up on his motorcycle, asking where I wanted to go.

I could walk on another ten hours from this place to Dhulikel, he said, but instead he could take me downhill on his bike to the direct road. I accepted his offer.

He saved my life.

Nala, the village where he dropped me, was quiet and sparsely populated. Everybody seemed to be out in the fields working. Small children and their mothers were in and around the homes.

Without warning, it happened. I was hit by a sudden wave of nausea and dizziness. It wouldn’t leave! Was this food poisoning? Hypoglycaemia? My knees wobbled, ready to give way. Trees looked like they were being shaken from the roots.

It was a few moments before people started screaming. The mountains rumbled and a cloud of dust began to rise from them.

The earth quaked.

It felt as though a strong force was trying to pin me to the ground with its powerful side-to-side agitation. Flower pots fell from terraces. The road groaned. Bikers toppled helplessly off their machines. Before my eyes, I saw fine cracks appear in the ground.

It felt as though a strong force was trying to pin me to the ground with its powerful side-to-side agitation. Flower pots fell from terraces. The road groaned. Bikers toppled helplessly off their machines. Before my eyes, I saw fine cracks appear in the ground.

From a house nearby, two men stumbled out onto the road, only to realise that there were children still indoors. I ran in with them and helped bring out three horrified children.

The ground was still shaking violently, so the only possible gait was a drunken stagger. Even when the shaking subsided, the earth underneath it continued to groan. Later I was told that the earthquake had lasted fifty-five seconds. That was the longest minute I have ever lived through.

Looking up at the hillside I had just biked down from, I saw it covered in a cloud of dust; rock, boulders and sand roaring downhill. I could see no trace of the houses I had passed on my ride down.

I spotted people who had been working in the fields running back towards the village. So far I had seen no casualties. But the earth wasn’t still. Every few seconds it rumbled and shook, though less strongly.

Rather than move on to Dhulikel, I decided to wait in an open field till the tremors had stopped. I sat there for an hour but the rumbling didn’t stop. My muddled brain tried to calm me down, saying that earthquakes like this were common in the Himalayas. Later I learned that the last ’quake of a similar magnitude was in 1934, eighty years in the past.

I didn’t know what to do, so I continued walking. I passed a small town called Banepa, where the highway showed cracks. People were all standing outside their houses. A few mud-walled buildings had been reduced to rubble, some windows had shattered and the shops were shuttered, but people did not look worried. Some were even excited.

Every time there was a tremor, though, the downed shutters would rattle hard, and the women would squeal in a loud chorus.

I reached Dhulikel four hours after the earthquake. Here too, just a few mud houses had crumbled, but public transport was overflowing with people. I realised later they were trying to get to the hospital. Everybody was out on the streets.

I bumped into a pair of Turkish tourists, father and son, who had found a taxi, and urged me to go back to Kathmandu with them. I told myself I could come back once the tremors stopped. Despite a highway full of cracks, it took only an hour to get to Kathmandu.

In the city, broken pavements and streets made it difficult to walk. When I saw the number of people waiting in front of the hospital, I realised that this was a much bigger calamity than I had thought. People were searching for kin in the rubble, ambulances were rushing bleeding victims to hospitals. They were the only vehicles on the road, other than the overcrowded buses.

I got out of the taxi and started walking towards the nearby government hospital. Mobile networks were down and the entire population seemed to be out on the streets, a mass of people sobbing and running around helplessly. Darkness fell, and only the occasional passing ambulance lit my way.

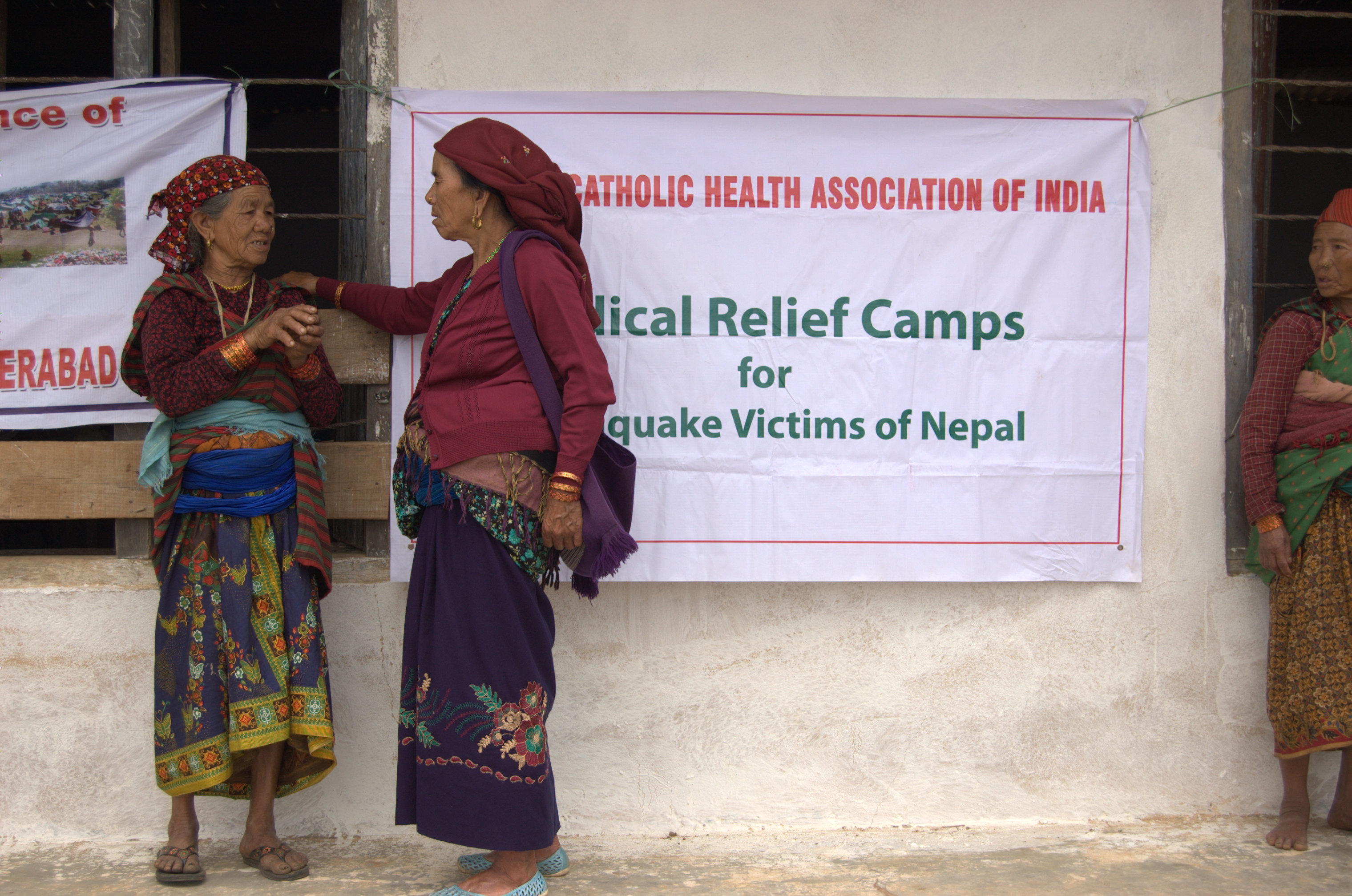

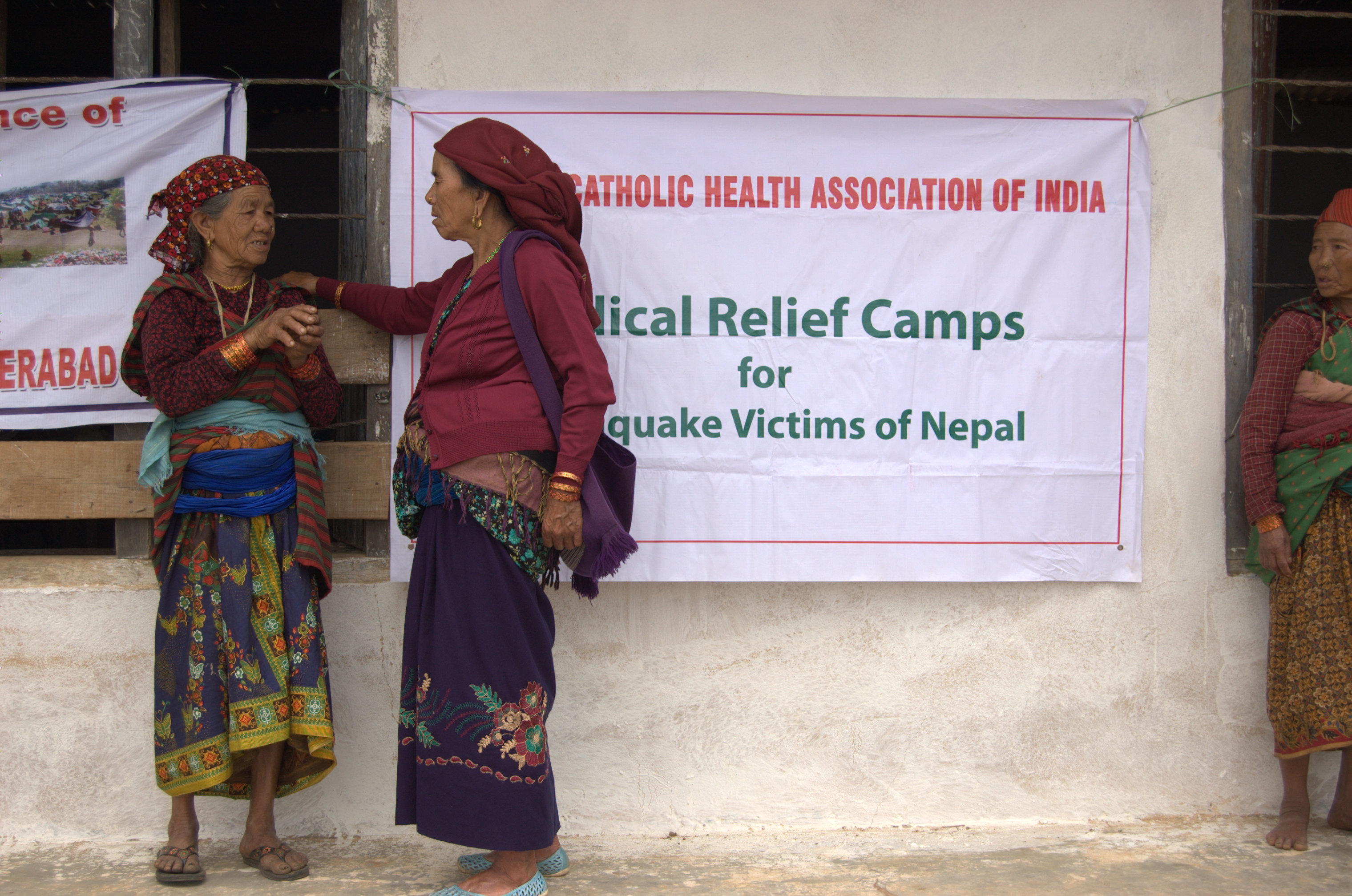

At the hospital, doctors, nurses and medical students were doing the best they could, as they moved from one patient to the next. They were short on supplies. And the injured and sick were still pouring in.

I met one of the staff, told them that I was a doctor and I could help. I shifted patients for scans, took blood samples, then went around adjusting and checking the intravenous fluid lines.

At some point I was assigned to an eight-year-old boy who needed a CT scan of his head immediately. There was only one elevator and it could accommodate only one stretcher at a time. We could not wait, so we piled three or more patients on to each stretcher. The little boy was laid down alongside a frail old lady.

Upstairs in the scan room there were a dozen people waiting on wheelchairs and trolleys. They took one look at our crowded stretcher and let us pass into the imaging room. When the staff asked whether I was this boy’s brother or father, I realised that his mother had been left behind downstairs.

The boy’s scan was soon done, but the old lady still had to get hers. I had to get the boy downstairs, back to his mother immediately, but there was no spare stretcher. Against everything I had learnt in medical school about moving patients with head injuries, I lifted him and carried him in my arms. His misshapen head rested softly against me, and his blood started to stain my shirt. After a few moments he began to get agitated, tugging at my shirt. I stood there helplessly, not knowing what to do and wanting to cry.

Back in the casualty ward I saw another boy, sitting on a bed crying. He was Indian, twelve years old and named Pappai. He was playing near his uncle’s home in Kathmandu when the earthquake hit. A collapsing building had fractured both his ankles. He was brought to the hospital by an ambulance and had no idea where his family was. He was terrified. All I could offer was a little consolation and a few carrots I had in my bag.

I was beginning to wonder where I would go myself. I couldn’t work in the hospital any more. I was near collapse myself and needed some rest, and there were enough medical staff at the hospital. I promised Pappai that I would come back and see him after a few hours and would make sure that he found his family. Luckily he remembered his father’s phone number. His father was in Kolkata.

I returned to the locality where I had stayed in Kathmandu earlier. Everyone was out in the open. I went to the locals, who heard my story and took me in, gave me their water and biscuits and the entire back seat of their car to sleep in. They sat inside their cars all night.

Miraculously, someone’s WiFi was still working! I read frantic messages from friends and family, and managed to send some replies. I asked one friend to contact Pappai’s parents in Kolkata.

The constant anxiety kept us awake the whole night. The car shook for a good ten seconds with each aftershock, even if it was just a brief tremor.

26 April 2015

The next morning I left my luggage at a Christian convent and returned to the hospital. There were still people on the roads, though luckily the tremors were fewer and weaker.

The hospital seemed much less chaotic. There were no more ambulances rushing towards the hospital, and no more patients waiting on gurneys. With difficulty I found the eight-year-old with the head injury; he was in the ICU. The wards were crowded, with injured people in every corner. I couldn’t find Pappai at all, and the nurses had no idea about him.

So I headed back to the convent, intending to set out for another hospital. On the way back, I passed the Dharahara Tower I had so wanted to climb. It took me a while to realise that the tower wasn’t rising above the trees. Someone told me that it had collapsed, killing 180 people. My blood froze for a second, thinking about the people inside who would have been walking up the spiralling stairs and felt the weight of the tower crashing down towards the earth. I could only hope that it was a quick death.

The army grounds nearby were littered with tents and each tent was packed with people.

It looked as though the staple food of the Kathmandu Valley had changed overnight to biscuits and raw instant noodles. Most people were living in the open.

And then it began to rain.

I remember seeing a young mother and her small daughter hugging each other, crying quietly, as if they had nobody left, nowhere to go.

Now — again! — shop shutters began to rattle loudly, and people began to scream. Another earthquake, this time for what felt like thirty seconds.

I sat down on the road, unable to control my knees.

I watched a four storey building no more than twenty feet away shake wildly, ready to fall in my direction. For the first time I was scared I would die. I don’t remember how I got back to the convent.

At the convent I was given a room. There I sat on the floor and, without warning, found myself sobbing uncontrollably.

So sure my brother could have had Marfans but it was more likely just a growth spurt. The 20 year old with blood in stool and weightloss could have cancer but it’s more likely a fissure in ano. Like a professor in Maryland once told his students, “When you hear hoof beats in Texas, think horses not zebras.”

So sure my brother could have had Marfans but it was more likely just a growth spurt. The 20 year old with blood in stool and weightloss could have cancer but it’s more likely a fissure in ano. Like a professor in Maryland once told his students, “When you hear hoof beats in Texas, think horses not zebras.”

It felt as though a strong force was trying to pin me to the ground with its powerful side-to-side agitation. Flower pots fell from terraces. The road groaned. Bikers toppled helplessly off their machines. Before my eyes, I saw fine cracks appear in the ground.

It felt as though a strong force was trying to pin me to the ground with its powerful side-to-side agitation. Flower pots fell from terraces. The road groaned. Bikers toppled helplessly off their machines. Before my eyes, I saw fine cracks appear in the ground.